It is easier to call it “development” than what it is.

On December 9, 2025, bulldozers tore through the riverside community of Oworonshoki in Lagos, Nigeria, flattening thousands of homes in a matter of minutes.

There was no notice. There was no meaningful consultation. There was no safe alternative offered to the people who lived there. What followed was not just eviction, but violence. Per NPR, police reportedly set fire to belongings residents tried to salvage, and community leaders say more than ten people died in the chaos. Some trapped inside their homes as they collapsed, others from medical emergencies triggered by the shock of displacement.

Nearly 10,000 people were made homeless in a single operation.

This was not a natural disaster. It was not an accident. It was a deliberate state action carried out in defiance of a standing court injunction that explicitly barred evictions until residents were consulted and rehoused.

According to the Justice & Empowerment Initiative, the Lagos state government ignored that ruling entirely. “The rule of law is not being respected,” the organization’s Megan Chapman said plainly in an interview with NPR.

And yet, the dominant language surrounding what happened in Lagos remains sanitized (if you heard about it at all).

Homes were “cleared.” Land was “reclaimed.” Compensation is allegedly “being processed,” even as residents say they have received nothing more than vague promises; reportedly as low as the equivalent of $150 per household, if it materializes at all.

This is how displacement becomes invisible: not by denying that harm occurred, but by stripping it of its meaning.

Displacement Without the Drama of War

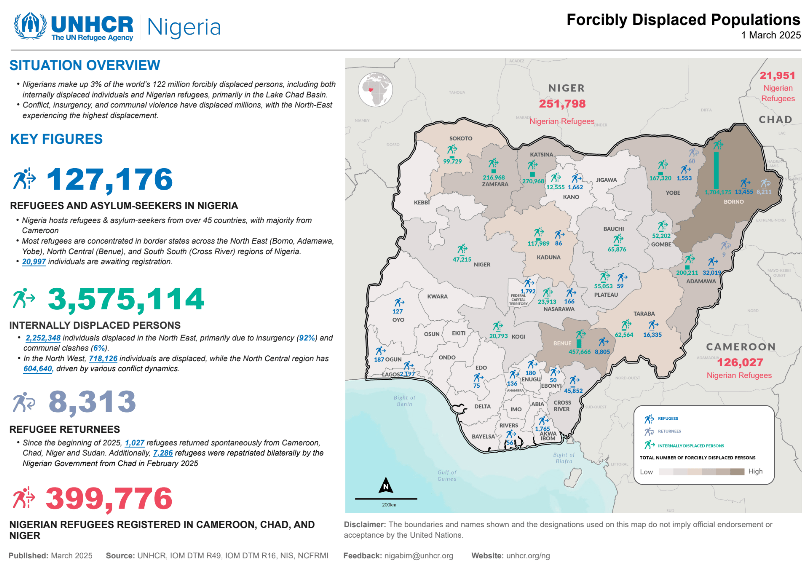

When people hear the phrase “internally displaced persons,” they tend to imagine armed conflict, insurgencies, or mass flight from war zones. Nigeria fits that picture all too well. According to Human Rights Watch, more than 1.3 million people were internally displaced in the northwest and north-central regions alone by April 2024, driven by banditry, mass kidnappings, and violent clashes. In the northeast, Boko Haram and ISWAP continue to kill civilians and uproot communities.

But Lagos disrupts the comforting fiction that displacement is something that happens only at the margins of the state. What happened in Oworonshoki shows that people can be forcibly displaced not because the government has lost control, but because it is exercising it.

The United Nations has long warned that internal displacement in Africa vastly outnumbers cross-border refugee flows. Aderanti Adepoju notes that internally displaced persons outnumber refugees on the continent by a ratio of five to one, and that Nigeria alone accounted for roughly 3.3 million IDPs as early as 2014; about 10 percent of the global total at the time.

Most of these people never cross a border. They do not trigger international crises or cable news countdowns. They simply lose their homes and are absorbed, uneasily, into other precarious spaces: overcrowded relatives’ houses, informal settlements even more vulnerable to eviction, or outright homelessness.

Lagos, a city of more than 20 million people, is particularly brutal in this regard. The World Bank estimates that up to 75 percent of Lagos residents live in informal housing, meaning the majority of the city exists in a state of permanent legal vulnerability.

When informal housing is treated as illegitimate by default, mass displacement becomes not an emergency, but an administrative option.

Law Exists…Until It Becomes Inconvenient

One of the most disturbing aspects of the Lagos evictions is not that they occurred, but that they occurred illegally.

As mentioned earlier, residents had already secured a high court injunction preventing evictions until consultation and resettlement took place. That ruling was not ambiguous. It was not pending. It was simply ignored.

This selective relationship to law mirrors broader patterns documented by Human Rights Watch. In 2024, Nigerian authorities repeatedly responded to public anger over economic hardship with repression rather than remedy.

Protesters were arrested, journalists detained, and critics targeted under the Cybercrimes Act. Even minors were initially charged with treason following the #EndBadGovernance protests.

The message is consistent: rights exist in theory, but only insofar as they do not interfere with political or economic priorities.

In Lagos, those priorities are painfully clear. While officials deny that evicted land will be used for luxury development, advocates on the ground have little doubt that waterfront property cleared of poor residents will not remain empty for long.

Development, in this model, is something done to people, not with them.

Economic Crisis as an Accelerant

The timing of these evictions matters.

Nigeria is currently experiencing its worst cost-of-living crisis in three decades. Following the 2023 election of President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, inflation surged to over 34 percent by mid-2024, with food inflation exceeding 40 percent. Government cash transfer programs reached only a fraction of the promised households, while public outrage intensified over elite spending priorities, including the purchase of a new presidential jet.

In this context, displacement is not just a loss of shelter. It is an economic death spiral. People who lose their homes also lose proximity to work, community support networks, and access to informal economies that make survival possible. For widows like Esther Lawal, whose three-bedroom home built with her late husband’s life savings, was destroyed in minutes, eviction is not a setback. It is erasure.

The government’s claim that minimal compensation will eventually be processed does little to address the reality that people need somewhere to sleep now.

Sovereignty, Security, and Selective Concern

At the same time Nigeria insists (correctly) that foreign governments misunderstand its internal complexities.

In late 2025, Nigerian officials pushed back forcefully against U.S. threats of military intervention following allegations of a “Christian genocide.” Information Minister Mohammed Idris Malagi rejected those claims, emphasizing that violence in Nigeria is not religiously targeted and is driven largely by competition over land and resources, exacerbated by climate change.

Nigeria has every right to reject crude, militarized narratives imposed from outside. But sovereignty does not absolve a state of responsibility for how it treats its own people…particularly when harm is inflicted not by insurgents, but by bulldozers under government authority.

You cannot credibly argue for cooperation over coercion abroad while normalizing forced displacement at home.

The Price of Calling It What It Is

What happened in Lagos will not be labeled a humanitarian crisis. There will be no emergency summits, no pledging conferences, no dramatic headlines about “waves” of displaced people.

That is precisely why it matters.

Internal displacement that does not cross borders is easy to ignore. It does not destabilize neighboring states or threaten Western domestic politics. It simply concentrates suffering among those least able to absorb it.

The people of Oworonshoki are now internally displaced persons, whether or not the government uses the term. They have lost homes, livelihoods, and legal protection in a city where most people already live one eviction away from catastrophe.

This is not a failure of development, but development revealing its priorities.

And unless it is named, challenged, and resisted, Lagos will not be an exception. It will be a blueprint.

Sources

Salako, P. (November 19, 2025). Cooperation not threats: Nigeria wants US alliance to curb violent attacks. Al Jazeera.

HRW Staff. (2025) Nigeria: Events of 2024, Human Rights Watch.

Adepoju, A. (2016). Migration Dynamics, Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons in Africa. United Nations Academic Impact.

Akinwotu, E. (December 9, 2025). Thousands of people in Lagos, Nigeria, have had homes abruptly seized and destroyed. Transcript of All Things Considered segment. NPR.

Various Authors. Lagos Platform for Development: Multi-Sector Analytical Review and Engagement Framework Overview. World Bank Group.

Leave a comment